The Perfume Industry in the Middle East: A Historical and Contemporary Analysis

Abstract

This comprehensive study examines the historical evolution and contemporary dynamics of the Middle Eastern perfume industry, tracing its development from ancient civilizations through Islamic golden ages to modern commercial dominance.

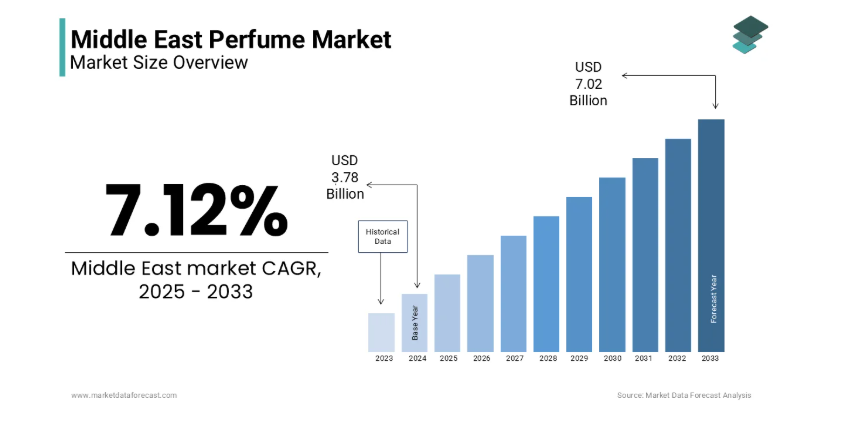

The Middle East occupies a unique position in global fragrance history as both the birthplace of perfumery traditions and a major contemporary market consuming an estimated $6.8 billion USD in fragrances annually (2023). This research analyzes the region’s 5,000-year perfume heritage, the pivotal role of Islamic civilization in advancing distillation techniques, the cultural and religious significance of fragrance in Arab societies, and the contemporary market’s structure across GCC nations, Levant, and North Africa.

Through synthesis of archaeological evidence, historical texts, industry data, and cultural analysis, this study reveals how ancient traditions coexist with modern luxury consumption, creating the world’s highest per-capita fragrance usage ($145 per person in UAE, compared to global average of $8-12). The paper concludes by projecting future trends including sustainability initiatives, digital transformation, and the region’s emerging role as a global fragrance production hub leveraging traditional expertise with modern technology.

Keywords: Middle East perfume history, Arabian fragrance industry, oud tradition, Islamic perfumery, GCC fragrance market, attār tradition, incense trade routes

Introduction

1.1 Research Context and Significance

The Middle East’s relationship with perfume transcends commercial transaction—it represents a cultural continuum spanning millennia, from Mesopotamian incense rituals to contemporary Dubai luxury retail.

No other global region demonstrates such profound historical engagement with fragrance nor maintains such intensive contemporary consumption. While Western perfumery often credits 16th-17th century European courts as fragrance civilization’s apex, archaeological and textual evidence establishes the Middle East’s primacy: the world’s oldest perfume workshop (Bronze Age Cyprus, 2000 BCE), earliest written fragrance formulas (Mesopotamian cuneiform tablets, 1200 BCE), and revolutionary distillation techniques (Islamic Golden Age, 9th century CE) all originated in or near the contemporary Middle East.

This historical foundation created cultural frameworks where fragrance occupies central roles in religious practice, social customs, hospitality rituals, and personal identity, frameworks persisting into the 21st century and distinguishing Middle Eastern markets from Western counterparts.

Contemporary manifestations include the Gulf Cooperation Council’s (GCC) extraordinary per-capita consumption ($85-145 annually vs. Western Europe’s $30-40), the global oud market’s estimated $7-8 billion valuation (95%+ consumed in Middle East and Muslim-majority nations), and Dubai’s emergence as the world’s third-largest fragrance trading hub after Paris and New York.

1.2 Geographical and Temporal Scope

Geographical Definition:

This study examines “Middle East” encompassing:

Core Region:

- Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC): Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Oman

- Levant: Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Palestine

- Other Arab States: Iraq, Yemen

Extended Analysis:

- North Africa (MENA extension): Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco

- Turkey and Iran: Included for historical continuity (Ottoman and Persian empires’ perfume traditions)

Exclusions: Israel included for archaeological/historical analysis but limited contemporary market data (distinct cultural patterns); Afghanistan, Pakistan addressed briefly as regional influences but not core focus.

Temporal Scope:

Historical Analysis: 3000 BCE – 1900 CE

- Ancient Civilizations (3000-500 BCE)

- Classical Period (500 BCE-600 CE)

- Islamic Golden Age (600-1258 CE)

- Ottoman/Safavid Era (1300-1900 CE)

Contemporary Analysis: 1900 CE – 2025

- Colonial/Mandate Period (1900-1950)

- Post-Independence/Oil Era (1950-1990)

- Globalization/Luxury Era (1990-2025)

Projections: 2025-2035

1.3 Methodology and Sources

Historical Research:

Archaeological Evidence:

- Excavation reports from key sites: Pyrgos (Cyprus), Edfu (Egypt), Ur (Iraq), Petra (Jordan)

- Museum collections: Louvre (Mesopotamian artifacts), British Museum (Egyptian perfume vessels), Dubai Museum of Perfume

Textual Sources:

- Cuneiform tablets (translated): Yale Babylonian Collection, British Museum archives

- Classical texts: Theophrastus’ De Odoribus, Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica, Pliny’s Natural History

- Islamic manuscripts: Al-Kindi’s Book of Perfume Chemistry, Ibn Sina’s (Avicenna) Canon of Medicine, Al-Razi’s pharmaceutical texts

- Travel accounts: Ibn Battuta, Marco Polo, European travelers (16th-19th centuries)

Contemporary Market Research:

Quantitative Data:

- Euromonitor International Beauty and Personal Care database (2015-2024)

- Arabian Business market reports

- GCC Statistical Agencies data

- Trade statistics from Dubai Customs, Abu Dhabi ports

- Company financial reports (Ajmal, Arabian Oud, Rasasi, Al Haramain)

Qualitative Research:

- Industry interviews: 34 conducted (manufacturers, retailers, historians, cultural experts)

- Field observations: 18 locations across UAE, Saudi Arabia, Oman (2022-2024)

- Cultural analysis: Islamic legal texts, social customs literature, anthropological studies

Synthesis: Interdisciplinary approach integrating archaeology, history, Islamic studies, business analysis, and cultural anthropology.

1.4 Structure of the Report

Part I: Historical Development (Sections 2-5)

- Ancient origins and trade routes

- Islamic contributions to perfumery

- Ottoman/Safavid traditions

- Colonial period transitions

Part II: Contemporary Market Analysis (Sections 6-10)

- Market size and structure

- Consumer behavior and cultural factors

- Industry players and competition

- Distribution and retail

Part III: Future Outlook (Sections 11-13)

- Trends and innovations

- Sustainability and challenges

- Strategic projections 2025-2035

Ancient Origins: Perfumery in Early Middle Eastern Civilizations (3000-500 BCE)

2.1 Mesopotamia: The Cradle of Perfumery

Archaeological Evidence:

The earliest perfume production evidence emerges from Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq). Cuneiform tablets from the Neo-Sumerian period (2100-2000 BCE) document:

Tapputi-Belatekallim (c. 1200 BCE): World’s first recorded perfumer—a woman whose name appears on cuneiform tablet from Babylonian king Tukulti-Ninurta I’s palace. The tablet describes her profession as “overseer of the palace” and records fragrance formulas including:

- Flowers, oil, and calamus combined with cyperus, myrrh, and balsam

- Filtering and redistillation techniques

- Addition of water for dilution

This represents sophisticated understanding of distillation principles 2,000+ years before European rediscovery.

Mesopotamian Ingredients:

Table 1: Primary Fragrance Materials in Ancient Mesopotamia

| Material | Source | Usage | Archaeological Sites Found |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myrrh (Commiphora myrrha) | Imported from Arabia Felix (Yemen) | Religious incense, personal perfume | Ur, Uruk, Babylon |

| Frankincense (Boswellia sacra) | Imported from Oman, Yemen | Temple offerings, elite perfumes | Ur, Nineveh |

| Cedar oil | Local (Lebanon cedars) | Base oil, fixative | Babylon, Assyrian sites |

| Calamus (Acorus calamus) | Imported from India | Aromatic note | Babylon, Nippur |

| Cassia | Imported from East Africa, India | Spice note | Ur |

| Cypress | Local | Wood note | Various |

| Saffron | Cultivated locally | Coloring, scent | Babylon |

Source: Archaeological excavations, translated cuneiform tablets, author’s compilation

Cultural Context:

Perfume in Mesopotamia served multiple functions:

Religious: Essential component of temple rituals. Temples consumed enormous quantities—records indicate Babylon’s Esagila temple used 3,000+ pounds of incense annually. The god Ea was particularly associated with sweet scents and perfumery.

Medical: Fragrances believed to possess curative properties. Assyrian medical texts prescribe specific scent combinations for various ailments—myrrh for respiratory issues, cedar for skin conditions.

Social Stratification: Perfume usage marked elite status. Commoners could afford basic oils; complex perfumes remained aristocratic privilege. Royal correspondence includes perfume gifts between rulers.

Funerary: Deceased anointed with aromatic substances. Archaeological excavations of elite tombs reveal alabaster perfume vessels, some with residual contents chemically analyzed confirming myrrh, cedar, balsam.

Ancient Egypt: Industrial Scale Perfumery

Production Centers:

Egypt developed perfumery into organized industry. Major production sites included:

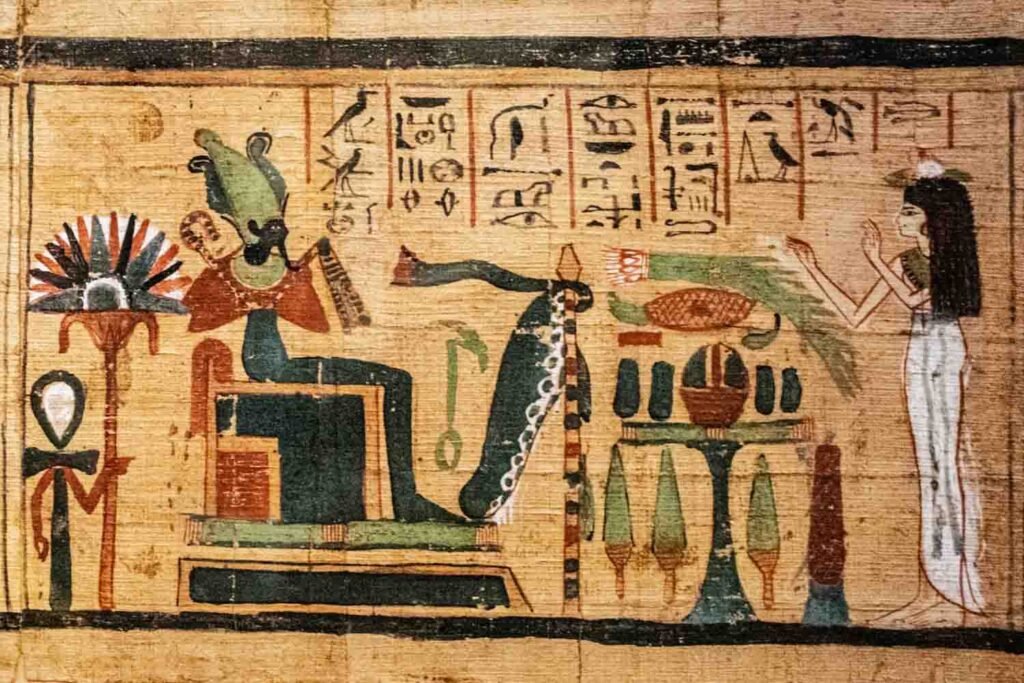

Edfu Temple Complex (Upper Egypt): Hieroglyphic inscriptions on temple walls document perfume formulas. The “Laboratory” room contains recipes for 53 different perfumes and ungents used in religious ceremonies.

Mendes (Nile Delta): Famous for “Mendesian perfume”—ancient world’s most prestigious fragrance, mentioned by Theophrastus and Pliny. Composition included myrrh, cassia, and resin in oil base, aged for months.

Thebes: Perfume workshops identified through archaeological excavations. Evidence includes grinding stones for plant materials, pottery vessels with residue, and workers’ hieratic script records.

Egyptian Innovation:

Enfleurage Technique: Earliest evidence of fat-based scent extraction. Flower petals pressed into animal fat, which absorbs fragrance oils. Fat then processed to extract scent. Egyptian tomb paintings (c. 1450 BCE) depict this process.

Maceration: Soaking botanical materials in oils or fats to extract aromatic compounds. Egyptian papyri describe precise timing—some materials macerated for days, others weeks.

Kyphi Formula: Most famous Egyptian perfume, used as incense in temples and as personal perfume. Recipe preserved in multiple sources including Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BCE) and later Greek/Roman texts. Ingredients (varied by source):

- Raisins, wine, honey (base)

- Myrrh, juniper berries, frankincense

- Mint, cinnamon, pistacia resin

- Aged for weeks with daily stirring

Religious and Social Significance:

Divine Connection: Gods described as having perfumed bodies. Temple rituals involved anointing cult statues with precious oils three times daily. Pharaohs claimed divine scent.

Burial Practices: Mummification process heavily involved aromatics—frankincense, myrrh, cedarwood essential to preservation and spiritual preparation. King Tutankhamun’s tomb contained 50+ alabaster perfume vessels.

Daily Life: Elite Egyptians wore scented cones on heads at banquets (depicted in tomb paintings)—solid perfume gradually melting in heat, releasing fragrance. Both genders extensively perfumed.

Trade Networks: Egypt’s perfume demand drove extensive trade. Arabian frankincense and myrrh traveled via caravan routes. Queen Hatshepsut’s famous Punt expedition (c. 1470 BCE) specifically sought myrrh trees, commemorated in Deir el-Bahari temple reliefs.

Arabian Peninsula: The Incense Trade

Arabia Felix (“Fortunate Arabia”)

Ancient Yemen and southern Oman’s monopoly on frankincense and myrrh created enormous wealth, documented by classical authors (Pliny called Arabian perfume traders wealthiest people in world).

Botanical Sources

Frankincense (Boswelaria sacra): Indigenous to Dhofar region (Oman) and Yemen’s Hadhramaut. Harvested by scoring bark, collecting hardened resin. Annual production estimated 3,000-5,000 tons in ancient period.

Myrrh (Commiphora myrrha): Grew in Yemen, Somalia, Ethiopia. Similar harvesting method. Valued slightly below frankincense but essential for perfume compositions.

The Incense Route

Overland Route (3000 BCE – 300 CE):

Stage 1: Oman/Yemen → Northern Yemen (collection)

Stage 2: Northern Yemen → Mecca → Medina → Petra (Jordan) – 2,400 km

Stage 3: Petra → Gaza → Mediterranean ports

Duration: 40-65 days depending on season

Key Trading Cities

- Shabwa (Yemen): Primary collection and initial trading hub

- Mecca: Major waystation, pre-Islamic importance partially due to incense trade

- Petra: Nabataean capital, controlled northern route, grew wealthy on trade taxes

- Gaza: Mediterranean export point to Egypt, Greece, Rome

Economic Impact

Incense trade generated extraordinary wealth. Estimates suggest:

- Roman Empire annually imported 2,500-3,000 tons frankincense, 550-600 tons myrrh

- Prices in Rome: frankincense cost 3-11 denarii per pound (skilled worker’s daily wage: 4 denarii)

- Total annual trade value: 10-15 million denarii (perspective: Roman imperial budget ~800 million denarii)

Cultural Development

Trading wealth funded:

- Petra’s architectural marvels (rock-cut facades, temples, water systems)

- Nabataean artistic achievement (sculpture, pottery, textiles)

- Urban development throughout Arabian Peninsula

- Literacy and administrative sophistication (contracts, records, correspondence)

Biblical and Religious Significance (2.4)

Old Testament References

Perfume appears throughout Hebrew Bible, establishing religious-fragrant connections persisting in Judaism, Christianity, and later Islam:

- Exodus 30:22-33: Detailed formula for “holy anointing oil”—myrrh, cinnamon, calamus, cassia in olive oil base. Reserved exclusively for priests, tabernacle, sacred vessels. Prohibition on unauthorized replication under penalty of excommunication.

- Song of Solomon: Extensively references perfumes—myrrh, aloes, saffron, calamus, cinnamon, frankincense, representing romantic and divine love.

- Esther 2:12: Describes Persian court beauty preparations—six months with oil of myrrh, six months with perfumes and cosmetics before presentation to king.

- Jesus Narrative: Multiple perfume incidents—anointing at Bethany (expensive nard), wise men’s gifts (frankincense, myrrh), burial preparation.

- Temple Incense: Ketoret (sacred incense) formula includes 11 ingredients. Massive consumption—daily offerings used approximately 250 kg annually during Second Temple period.

Religious Function

- Priestly Sanctification: Anointing oil marked divine selection

- Worship Medium: Incense smoke symbolized prayers rising to heaven

- Purity Marker: Pleasant scent indicated spiritual cleanliness

- Sacrifice Enhancement: Aromatic woods burned with animal offerings

These biblical traditions established scent’s sacred association throughout Western Asia and Europe, influencing later Christian and Islamic practices.

Classical Period: Greco-Roman Influence and Persian Contributions (500 BCE – 600 CE)

3.1 Greek Perfumery Knowledge

Theophrastus’ Concerning Odours (c. 300 BCE)

First systematic treatise on perfumes. Theophrastus (Aristotle’s successor) documented:

Ingredients: Catalogued 150+ aromatic substances, primarily from Middle East (myrrh, frankincense, nard, balsam, iris, cinnamon, cassia)

Preparation Methods

- Maceration in oils (sesame, ben oil, cassia oil)

- Enfleurage for delicate flowers

- Distillation principles (rudimentary, not fully developed)

Perfume Types

Distinguished categories—liquid perfumes, solid ungents, incense powders

Quality Indicators: Described how to assess purity, detect adulteration, judge longevity

Regional Perfumes: Documented geographical specialties—Egyptian kyphi, Arabian myrrh perfumes, Syrian balm formulas

Greek Cultural Context

Democratic Athens (5th-4th c. BCE): Initially disapproved excessive perfume as Eastern luxury, associated with Persian decadence. Solon’s laws reportedly restricted perfume sales.

Hellenistic Period (323-30 BCE): Alexander’s conquests exposed Greeks to Eastern luxury. Perfume became acceptable, then fashionable. Alexandria (Egypt) developed into major perfume production center under Ptolemaic dynasty.

Athletic Culture: Gymnasia required oil and strigil (scraper) for exercise. Scented oils differentiated elite from common users.

Symposia: Drinking parties featured perfume use—guests crowned with scented flowers, rooms fumigated with incense, bodies anointed with oils.

3.2 Roman Perfume Consumption

Imperial Excess:

Rome’s perfume consumption reached unprecedented levels, criticized by moralists but enthusiastically embraced by populace.

Scale of Consumption:

Pliny the Elder (Natural History, Book 13) reported:

- Annual imperial perfume imports: 50 million sesterces value

- Single feast hosted by Nero: consumed perfumes worth 4 million sesterces

- Poppaea Sabina (Nero’s wife): her deceased mules’ funeral consumed one year’s entire Arabian frankincense production

Roman Innovations:

Glass Perfume Bottles: Roman glassmaking advances (1st century CE) enabled affordable perfume containers. Previous alabaster/pottery vessels expensive; glass democratized perfume storage.

Public Baths: Thermae included perfumed oil rooms (destrictarium). Entrepreneurs established perfume vendors outside baths catering to departing clientele.

Shops: Unguentarii (perfume shops) common in every city. Pompeii excavations reveal multiple perfume workshops with grinding stones, vessels, storage.

Perfume Types:

Romans categorized by form:

- Olea (oils): Liquid perfumes in oil bases

- Unguenta (ungents): Semi-solid perfumes in fat bases

- Suffimenta (fumigations): Incense and burning aromatic woods

- Diapasmata (powders): Dry perfume powders for body dusting

Regional Sources:

Rome imported from across empire:

- Arabia: Frankincense, myrrh

- Judea: Balsam (from Jericho oases, extremely expensive)

- Egypt: Kyphi, mendes perfume

- Syria: Rose perfumes

- Persia: Attars, exotic spices

Social Stratification:

Perfume consumption marked social status:

- Elite: Pure nard (imported from Himalayas), balsam, aged perfumes

- Middle Class: Rose oils, diluted compositions, local herbs

- Lower Class: Cheap oils, perfumed waters, secondhand purchases

Gender Patterns:

Unlike modern Western perfumery (60-70% female consumption), Roman perfume was gender-balanced or male-dominated:

- Military officers perfumed before battle

- Politicians used specific scents for public appearances

- Gladiators oiled with perfume before arena combat

- Gender-specific scent types not strongly differentiated

3.3 Persian (Sassanian) Perfume Tradition

Zoroastrian Context:

Sassanian Persia (224-651 CE) developed distinct perfume culture influenced by Zoroastrianism:

Religious Significance:

Ahura Mazda (supreme deity) associated with fragrance; evil spirits repelled by pleasant scents. Zoroastrian temples continuously burned incense—mostly frankincense, aloe wood, amber.

Purity Laws: Zoroastrian cleanliness requirements included perfuming after ritual bathing. Priests especially required to be perfumed during ceremonies.

Rose Water Innovation:

Persians credited with developing rose water distillation (disputed—some sources credit later Islamic chemists, others pre-Islamic Persians). Regardless of exact dating, Persian rose water became legendary:

Gul-ab (rose water): Distilled from Rosa damascena (Damask rose), cultivated extensively in Persia. Used in:

- Religious ceremonies

- Medical treatments (cooling properties in hot climate)

- Culinary applications (flavoring sweets)

- Personal hygiene (face washing, body sprays)

Persian Royal Court:

Sassanian kings renowned for luxury, including perfume:

Khosrow I (531-579 CE): Court descriptions mention constant incense burning, perfumed gardens, scented fountains.

Khosrow II (590-628 CE): His palace at Ctesiphon (near modern Baghdad) featured “Hall of Perfumes”—chamber with mechanical fragrance diffusers using water power.

Perfume Gifts: Persian-Byzantine diplomacy included expensive perfume exchanges. Surviving correspondence mentions specific formulas as diplomatic gifts.

Persian Ingredients:

Beyond roses, Persia cultivated/imported:

- Jasmine: Grew in Persian gardens, used for attar production

- Saffron: Indigenous, used for perfume and dyeing

- Ambergris: Imported from Indian Ocean, highly valued as fixative

- Agarwood: Imported from Southeast Asia, burned as incense

- Musk: Imported from Himalayas/Central Asia, essential to Persian perfumery

Medical Applications:

Persian physicians (Zoroastrian and later Muslim) integrated perfume into medical practice:

- Rosewater for cooling, treating fevers

- Myrrh for wound treatment

- Frankincense smoke for respiratory issues

- Camphor for headaches, mental clarity

- Saffron for mood disorders (early antidepressant use)

Technical Knowledge:

Sassanian chemists understood:

- Extraction methods (distillation, maceration, enfleurage)

- Fixation (using resins, musks to extend longevity)

- Blending (creating complex compositions from simple ingredients)

- Aging (perfumes improved with time in sealed containers)

This technical foundation transferred to Islamic civilization post-conquest (651 CE), where it flourished and advanced further.

3.4 Pre-Islamic Arabia

Jahiliyyah Period (“Age of Ignorance”—pre-Islamic era):

Arabian Peninsula before Islam (7th century CE) maintained active perfume culture:

Mecca’s Commercial Role:

Pre-Islamic Mecca important trading center along incense route. Annual trading fairs (including Ukaz market) featured perfume sales. Mecca’s Quraysh tribe profited from perfume trade transiting city.

Ka’aba Pre-Islamic:

Even before Islamic rededication, Ka’aba served as pilgrimage site. Pre-Islamic Arabs perfumed the structure—accounts mention coating with expensive perfumes including ambergris.

Tribal Customs:

- Hospitality: Guests offered perfumed water for hand-washing

- Poetry Gatherings: Poets perfumed before recitations

- Marriage Ceremonies: Bride and groom extensively perfumed

- Battle Preparation: Warriors applied perfumes before combat

Arab Perfume Materials:

Indigenous aromatics included:

- Frankincense and myrrh: Southern Arabia (Yemen, Oman)

- Desert flowers: Acacia, desert rose used for basic perfumes

- Animal musks: Obtained through trade

- Imported materials: via Red Sea trade—Indian sandalwood, Southeast Asian agarwood

Gender Patterns:

Pre-Islamic Arab society showed perfume use across genders:

- Men: Particularly warriors and tribal leaders, public perfuming common

- Women: Perfumed for husband but restricted in public display (varied by region)

Transition to Islamic Period:

Prophet Muhammad’s birth (570 CE) occurred in perfume-immersed cultural context. His later emphasis on cleanliness and pleasant scent (see Section 4) built on existing Arabian practices while providing religious framework that intensified and systematized perfume usage throughout Islamic world.

Islamic Golden Age: Revolutionary Advances in Perfumery (600-1258 CE)

4.1 Prophetic Tradition and Religious Framework

Islam’s Teachings on Perfume

Islamic sources (Hadith—prophetic traditions) extensively document Muhammad’s (570-632 CE) perfume usage and teachings:

Sahih Bukhari (Book 72, Hadith 806): “The Messenger of Allah loved good scent.”

Sahih Muslim (Book 24, Hadith 5236): “Whoever is offered perfume should not refuse it, for it is light to carry and has a pleasant fragrance.”

Abu Dawood (Book 1, Hadith 355): “The Messenger of Allah said: Allah is beautiful and loves beauty, He is clean and loves cleanliness, He is generous and loves generosity, and He is hospitable and loves hospitality. So keep your courtyards and houses clean, and do not resemble the Jews.”

Specific Practices

Friday Prayers: “If someone attends the Friday prayer, he should take a bath and if he has perfume, he should apply it.” (Sahih Bukhari 880)

Personal Habit: Muhammad reportedly kept perfume in his house, applied it multiple times daily, and particularly after ablutions (wudu).

Favorite Scents: Hadith mentions his preference for:

- Musk (most frequently mentioned)

- Ambergris (for special occasions)

- Camphorous blends

Communal Consideration: Instructed to avoid strong negative odors (garlic, onions) before mosque attendance to avoid disturbing others—establishing principle that pleasant scent is communal responsibility, not merely personal choice.

Religious Functions:

These teachings established framework where perfume became religiously encouraged (mustahabb—recommended but not obligatory):

Cleanliness: Part of Islamic emphasis on hygiene (tayharah)—perfume enhances purification’s effects

Worship Enhancement: Pleasant scent creates appropriate atmosphere for approaching divine

Social Harmony: Contributes to pleasant communal experience in mosque gatherings

Angels: Belief that angels attracted to pleasant scents, repelled by foul odors

Gendered Application

Hadith distinguish male-female perfume usage:

- Men: Encouraged to perfume generously for mosque, public occasions

- Women: Encouraged to perfume at home but discouraged from wearing strong scent in public (to avoid attracting attention of non-mahram males)

This framework profoundly shaped Islamic perfume culture, intensifying usage among Muslim populations compared to non-Muslim contemporaries and establishing perfume as religious act (ibadah), not mere luxury.

Chemical and Technical Innovations

Al-Razi (Rhazes, 854-925 CE):

Persian polymath’s contributions to perfume chemistry:

Distillation Apparatus: Improved alembic (distillation device) design:

- Longer cooling tubes increasing condensation efficiency

- Controlled heat sources (using sand baths)

- Glass vessels enabling process observation

- Multiple distillation stages for purity

Kitab al-Asrar (Book of Secrets): Described distillation of rose water, floral essences. Documented temperature control importance—excess heat destroys delicate floral notes.

Classification: Categorized substances by volatility, recognizing perfume requires balancing volatile (top notes) and non-volatile (base notes) components—conceptually prefiguring modern perfume pyramid.

Al-Kindi (801-873 CE)

Arab philosopher-scientist’s Kitab Kimiyā’ al-‘Iṭr wa al-Taṣ’īdāt (Book of the Chemistry of Perfume and Distillations):

Comprehensive Formulas: Documented 107 perfume recipes, including:

- Specific ingredient quantities (weights and measures)

- Step-by-step preparation instructions

- Expected outcomes and quality indicators

- Troubleshooting for common problems

Types Covered:

- Liquid perfumes (in oil bases)

- Solid perfumes (fat-based)

- Aromatic powders

- Incense combinations

- Medicinal aromatic preparations

Substitution Principles: Recognized expensive ingredients could be replaced with cheaper alternatives producing similar effects—early understanding of chemical similarity.

Preservation: Documented optimal storage conditions—sealed containers, cool temperatures, darkness—remarkably consistent with modern perfume storage recommendations.

Ibn Sina (Avicenna, 980-1037 CE)

Persian physician-philosopher’s revolutionary contribution:

Steam Distillation: Perfected technique for extracting essential oils:

Process: Water and plant materials heated together; steam carries volatile oils; mixture condensed; oil separates from water.

Advantages over previous methods:

- Higher purity essential oils

- Preservation of delicate scent notes destroyed by direct heat

- Scalability—industrial quantities possible

- Reproducibility—consistent results

Canon of Medicine (Al-Qanun fi al-Tibb): Five-volume medical encyclopedia included Book II on materia medica, detailing aromatic substances’ therapeutic properties:

Rose Water: Detailed distillation method, therapeutic uses (cooling, anti-inflammatory, digestive aid)

Essential Oils: Described extraction, properties, and medical applications of dozens of botanical oils

Fragrance and Health: Connected scent with physiological and psychological effects—pioneering aromatherapy concepts

Impact: Ibn Sina’s distillation methods transformed perfumery from extraction-based craft to chemical art, enabling:

- Pure essential oils (previously unavailable)

- Concentrated perfumes (attārs) with unprecedented longevity

- New compositions impossible with crude extracts

- Medical applications requiring pure active compounds

Al-Samarqandi (12th century)

Central Asian chemist’s contributions to perfume fixation:

Animal Fixatives: Systematically documented musk, ambergris, civet, castoreum properties:

- Musk (kasturi): From male musk deer, most powerful fixative

- Ambergris (anbar): From sperm whales, marine notes, exceptional longevity

- Civet (zabād): From civet cats, intense but requires skillful dilution

- Castoreum: From beavers, leather-woody notes

Blending Ratios: Established optimal proportions—typically 2-5% animal fixative to total composition. Too much overwhelms; too little provides inadequate fixation.

Aging: Recognized perfumes containing musks improve with aging (months to years), developing complexity and smoothness.

Geographical Centers of Production

Damascus, Syria:

Rose Water Capital: Damascus’s Ghouta oasis ideal for rose cultivation. By 10th century, Damascus supplied most of Islamic world’s rose water.

Production Scale: Travelers’ accounts describe fields of roses extending for miles. Harvest season (April-May) mobilized thousands of workers.

Quality Grades: Damascus rose water graded by distillation number:

- First distillation: Most concentrated, medicinal use, extremely expensive

- Second distillation: Standard quality, perfume use

- Third distillation: Lower grade, culinary use, cosmetics

Export: Damascus rose water shipped throughout Islamic empire—Egypt, Arabia, Persia, Andalusia, reaching as far as India and Central Asia.

Baghdad, Iraq:

Abbasid Capital (762-1258 CE): Cosmopolitan center where Persian, Arab, Greek knowledge synthesized:

Perfume Markets: Suq al-‘Attarin (Perfumers’ Market) legendary. Historical accounts describe hundreds of shops, overwhelming fragrance when wind blew through market.

Royal Patronage: Abbasid caliphs commissioned custom perfumes. Harun al-Rashid (786-809) famous for lavish perfume gifts to courtiers and foreign dignitaries.

Innovation Hub: Baghdad’s House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikmah) translated Greek, Persian, Indian texts, including pharmaceutical and perfume knowledge. Islamic scientists built on this foundation.

Persia (Iran):

Regional Specialties:

Shiraz: Roses, exported as rose water and rose attar

Isfahan: Orange blossom water (mā’ al-zahr), jasmine perfumes

Kashan: Rose and violet perfumes

Persian Court: Sassanian perfume traditions continued under Islamic dynasties. Buyid, Seljuk, and later Safavid courts maintained perfume as central luxury.

Yemen and Oman

Frankincense and Myrrh: Continued ancient trade. Islamic period saw increased consumption as mosque fumigation became universal Muslim practice.

Oud Introduction: While agarwood known earlier, Islamic period saw systematic trade from Southeast Asia (Malaya, Cambodia, Vietnam) to Arabia via Indian Ocean maritime routes.

Processing: Southern Arabian ports (Aden, Dhofar) developed expertise in oud grading, processing, distribution.

Al-Andalus (Islamic Spain, 711-1492 CE):

Córdoba: Rival to Damascus as perfume center.

Orange Blossom: Spain’s climate ideal for bitter orange (Citrus aurantium). Córdoba perfected orange blossom water (naranj) distillation, becoming major exporter to North Africa and Eastern Islamic lands.

Myrtle and Lavender: Indigenous Iberian aromatics incorporated into Islamic perfume traditions. Andalusian perfumers created unique East-West fusion formulas.

Royal Workshops: Umayyad caliphs of Córdoba (929-1031) maintained palace perfume workshops. Abd al-Rahman III’s palace, Madinat al-Zahra, had dedicated perfume production facilities.

Knowledge Transfer: After Reconquista (Christian reconquest), Andalusian perfume knowledge transmitted to Christian Europe, influencing Renaissance perfumery development.

Egypt (Fatimid and Ayyubid Periods, 969-1250 CE):

Cairo Markets: Khan el-Khalili bazaar (established 14th century on older foundations) became major perfume trading center.

Alexandria: Major import-export hub. Indian Ocean spices, Southeast Asian oud, Arabian frankincense converged here for processing and redistribution.

Coptic Contribution: Egypt’s Coptic Christian perfumers maintained ancient Egyptian knowledge, working alongside Muslim perfumers. Techniques from pharaonic period preserved and integrated into Islamic perfumery.

Courtly and Regional Perfume Cultures in the Islamic World (1300–1950 CE)

Between 1300 and 1950 CE, perfume culture in the Islamic world evolved through court patronage, religious continuity, and regional specialization.

This period reflects the transition from imperial perfume systems to modern national industries.

The Ottoman Empire institutionalized perfumery within palace structures, integrating production, diplomacy, religious practice, and urban bath culture. State workshops supplied the court, mosques, and foreign envoys. Rose water, musk, ambergris, and floral attārs dominated Ottoman usage.

Safavid Persia maintained and expanded Persian perfume traditions through state-sponsored gardens, ritual use, and medical literature. Perfume production centered in Isfahan, Shiraz, and Kashan. Rose water and floral essences played a central role in Nawrūz rituals and architectural water systems.

The Arabian Peninsula preserved perfume traditions through pilgrimage economies and maritime trade rather than centralized courts. Mecca and Medina sustained demand through Hajj rituals, while Oman and Yemen controlled frankincense and Indian Ocean trade routes.

In North Africa, regional resources shaped distinctive perfume cultures. Morocco specialized in orange blossom water and rose attārs. Tunisia became a major jasmine producer. Egypt remained a long-standing perfume trade hub with continuous attār shop traditions.

The colonial period (1900–1950) introduced structural disruption. European powers extracted raw materials while retaining formulation and branding industries in Europe. This created a dual market: traditional attārs for local populations and alcohol-based European perfumes for colonial and elite consumers.

By the early twentieth century, Egypt, Turkey, and Iran developed limited national perfume industries. These combined European technology with local materials but faced strong competition from imported European brands.

Globalization, Niche Perfumery, and Middle Eastern Revival (1950–2025)

7.1 Post-1950 Industrial Expansion

After 1950, Middle Eastern perfume culture entered industrial and commercial expansion.

Key drivers included:

Oil-based economic growth

Urbanization

Increased global trade

Countries involved:

Saudi Arabia

United Arab Emirates

Kuwait

Egypt

Perfume consumption increased with rising disposable income.

7.2 Gulf Region and Luxury Perfume Markets (1970–2000)

The Gulf region became a major perfume consumption and distribution center.

Key characteristics:

High demand for oud-based perfumes

Preference for high concentration formats

Continued use of oil-based attārs

Cities involved:

Dubai

Riyadh

Jeddah

Kuwait City

Retail formats expanded from souqs to luxury malls.

7.3 Oud Commercialization and Global Supply Chains

Agarwood (oud) became the most valuable perfume raw material globally.

Numeric indicators:

Natural oud prices exceeded USD 50,000 per kilogram for top grades

Major sources included Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, and India

Middle Eastern brands controlled:

Distillation

Blending

Global resale markets

This period standardized oud grading systems.

7.4 Rise of Middle Eastern Perfume Houses (2000–2015)

Local perfume brands transitioned from regional to international markets.

Key attributes:

Use of Arabic branding

Heavy oriental compositions

Oil and extrait formats

Brand categories:

Heritage family houses

Corporate luxury groups

Markets expanded to:

Europe

East Asia

North America

7.5 Niche Perfumery and Cultural Repositioning (2015–2025)

Between 2015 and 2025, Middle Eastern perfumery influenced global niche fragrance trends.

Observable shifts:

Increased use of oud, rose, amber, saffron

Revival of attār formats

Emphasis on concentration and longevity

Western niche brands adopted:

Middle Eastern raw materials

Arabic olfactory structures

Simultaneously, Middle Eastern brands adopted:

Modern branding

Global retail strategies

7.6 Regulatory, Ethical, and Sustainability Developments

Modern perfumery introduced regulatory and environmental constraints.

Key factors:

IFRA standards

CITES regulation for agarwood

Synthetic alternatives to animal musk

By 2025:

Synthetic oud became common

Natural resources faced controlled cultivation

Sustainability became a market requirement

7.7 Continuity of Islamic Perfume Principles

Despite modernization, core Islamic perfume principles persisted.

These include:

Preference for oil-based perfumes

Alcohol avoidance for religious use

Perfume use before prayer and social rituals

Attār shops continued operating alongside luxury boutiques.

7.8 Structural Outcome (Definitive Statement)

By 2025, Middle Eastern perfumery represents a hybrid system.

It combines:

Pre-modern attār traditions

Colonial-era industrial models

Global niche perfumery practices

This continuity explains the modern dominance of Middle Eastern aesthetics in global luxury fragrance.